Imagine heading into the sunset – out of your ordinary life and sailing across the Pacific. Mai-Tais and tropical island oases await, with exotic cultures and welcoming new friends. But, of course, getting there is half the fun. You could hop on a 747 – but where’s the adventure? It’s that Pacific passage that makes the dream special to a sailor.

What does it take to cross the world’s biggest ocean? How do you even go about managing such a gargantuan journey? Here are some of the ways other cruisers have done it and a few of the widely-used sailing routes across the Pacific.

Table of Contents

- Cruising Across the Pacific by Sailboat

- Wind and Currents of the Pacific Sailing Routes

- Geography and Points of Interest on the Pacific Circuit

- Sailing Routes Across the Pacific Ocean

- Cruising Across the Pacific – The Ultimate Nautical Adventure

- Pacific Sailing Routes FAQs

Cruising Across the Pacific by Sailboat

Crossing the biggest ocean on the planet in a tiny sailboat is nothing to take lightly. But it’s also one of the biggest adventures you could imagine, so it’s no wonder that many people want to know how long does it take to sail across the Pacific?

Figuring how long to sail across Pacific is more complicated than you might imagine. The Pacific is home to some of the most beautiful and exotic cruising destinations in the world. As a result, it’s hard to pick just one destination, and most sailors crossing the Pacific Ocean are planning their route based on the sights they want to see.

When you break the Pacific crossing into legs, the longest leg is about three weeks of non-stop sailing. But before or after that, you may stay in one country or port for a few weeks to a month. And there are many more places to stop and many more long legs to make.

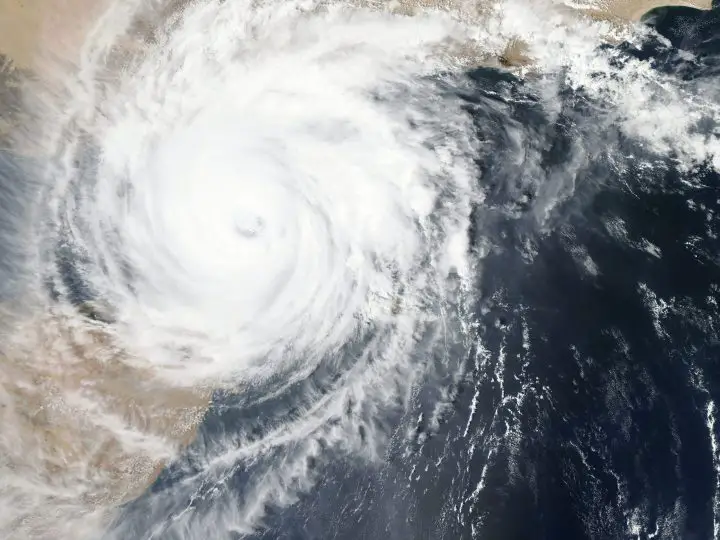

This must also be weighed with the weather and planning to avoid potential problems. The favored approach is to not travel during hurricane or cyclone season. During those months, you’ll want to be somewhere else or leave the boat in a secure location where you won’t have to worry about its safety should a storm pop up.

The result is that cruisers who set out to explore the Pacific are heading out on a long-term adventure. Most dedicate several years to it. If cruisers are young, they may be on a cruising sabbatical—a break from everyday life to enjoy the adventure while they’re still young. Of course, plenty of people also plan carefully and set off upon retirement. However and whenever you do it, it’s not something you can make up on the fly.

How Big of a Boat to Cross the Pacific?

The size of the boat isn’t the most critical factor when sailing across the Pacific. The size of the boat will factor into your comfort onboard and the number of supplies and other people that you can take along.

More important factors will be the safety of the vessel and its seaworthiness. How well made is it, and is it well-maintained? Is it equipped for an ocean voyage, with redundant and reliable systems, safety gear, and supplies for total self-sufficiency? Is the boat sturdy enough to come through unscathed if you encounter an unexpected storm?

An adventurous soul could tackle sailing routes Pacific (or otherwise) in a pocket cruiser sailboat for reference. Just because these boats are small—usually under 30 feet—doesn’t mean they can’t be serious bluewater cruisers.

Of course, crossing in small boats is the exception rather than the rule. Most sailors and sailing couples prefer boats between 40 and 50 feet for long-term voyaging. You can find a few good examples on our best bluewater cruising sailboats list.

Wind and Currents of the Pacific Sailing Routes

As with all long-distance voyaging via sailboat, understanding the prevailing wind conditions is critical to planning your trip. Sailing into the wind, or sailing to weather as sailors say, is rough work. It’s hard on the boat, hard on the crew, time-consuming, and tedious.

Most boats perform best on a reach—that is, with the wind coming from the side of the boat. This provides the best speeds and sailing performance. But most sailors prefer the ride when the boat sails downwind on a run. Speed is slower, but the boat’s motion is relaxing, with the waves instead of opposing them.

For this reason, given their choices, cruising sailors will choose to keep the wind aft of their beams when making passages. Of course, this might sometimes mean waiting for the right “weather window” before departing. But it always means playing your cards right depending on what part of the world you are transiting.

Winds are more consistent than most landlubbers give them credit for. The concept of tradewinds was born out over the generations as mariners discovered that winds blew in specific directions most of the time. Know the direction of the prevailing winds, and pick your destinations accordingly.

Pacific Trade Winds

In the North Pacific, the prevailing trade winds blow from the northeast from the equator to about 30-degrees north latitude. At higher latitudes, the winds blow from the southwest.

Around the equator, the trade winds meet in a zone of rising air known as the Intertropical Convergence Zone, or ITCZ. You might have heard sailors refer to this area as the doldrums. It is here that ships can get stuck for days or weeks in shifty light winds and dead calms.

Once farther south into the South Pacific, the trade winds mirror those on the north side. From the equator to 30-degrees south latitude, winds are the southeast trade winds. In the Southern Ocean, westerly winds blow in an area known as the Roaring Forties.

Currents

Also important to planning a voyage is understanding the world’s ocean currents. For example, when your vessel moves at seven knots, it’s a good idea not to oppose two-knot currents. Using it to your advantage, on the other hand, could improve your speed over the ground by more than 25 percent!

In the North Pacific, currents generally flow around the basin in a clockwise fashion. The North Equatorial current runs westbound with its axis around 12 degrees north latitude. The Kuroshio flows north towards Taiwan and Japan. It then bends west, turning into the North Pacific Current. Finally, it follows the coast of North America southbound as the California Current.

In the South Pacific, everything works counterclockwise. The South Equatorial Current runs west near the equator. Below the islands of the South Pacific in the Roaring Forties, the current sets eastbound. Most of it flows south of Cape Horn and into the Atlantic, but a portion runs northbound along the coast of South America.

Tropical Systems and Seasons to Avoid

The topical North and South Pacifics have their own cyclone seasons to avoid. Storms in the eastern North Pacific are referred to as hurricanes, while those in the western North Pacific are called typhoons. Hurricane season for the eastern Pacific is from May to November. The eastern Pacific typhoons are stronger and more common than any other tropical storm in the world. Most typhoons occur from May to December, but they can actually happen during any month of the year.

Storms in the South Pacific are usually called cyclones. The official cyclone season runs from November until the end of April – although most seasons have lasted longer in recent years.

Geography and Points of Interest on the Pacific Circuit

Before diving into the routes one can take, understanding the destinations helps clarify the trip. Only the most dedicated racers or delivery skippers make an uninterrupted crossing. For most folks, crossing the Pacific is about stopping in exotic ports of call as much as it is about the adventure of the crossing.

While a more extensive list of the destinations around the Pacific lies below, there are several key points that will help to understand the geography of the routes. For example, Tahiti, the capital of French Polynesia, is located at roughly the halfway point in the South Pacific. Due north of it, on the other side of the equator, is the Hawaiian Islands.

On the west coast of the Americas, from north to south, you will find:

- Alaska and the Inside Passage

- Pacific Northwest of the North America

- California

- Mexico, Central America, and the Panama Canal

- Ecuador and Galapegos Islands

- Chile and Easter Island

The South Pacific Islands, stretching from east to west, include:

- French Polynesia, including the Marquesas Islands, Tuamotu Islands, Society Islands (Tahiti and Bora Bora)

- Line Islands

- Cook Islands

- Niue

- Samoa

- Tonga

- Fiji

- Vanuatu

- New Caldonia

- Solomon Islands

- Papua New Guinea

- Micronesia

- Hawaii is an outlier, sitting north of the equator and several weeks of sailing north from Tahiti

In the extreme southwest Pacific:

- New Zealand

- Australian Coast

In the western Pacific and southeast Asia, going from south to north:

- Indonesia

- Philippines

- Palau

- Coral Sea

- Malaysia

- Japan

Sailing Routes Across the Pacific Ocean

Once you account for the wind and current patterns in the Pacific, a circuit route becomes the obvious choice. Beginning on the West Coast of the US, most routes go south before beginning a westbound crossing in the prevailing southeasterlies.

Coming home, most boats travel north until they are in Hawaii or near Japan before turning for the US West Coast. Altogether, this makes one giant circle around the whole ocean.

Westbound Pacific Ocean Crossing

So if you are leaving the west coast of the Americas, your planned route will greatly depend on your ultimate destination. If you’re leaving the Pacific Northwest or California bound for Hawaii, a direct route might be an option. Sailing to Hawaii from California is fairly straightforward. Once beyond the shifting winds common near the mainland, consistent northeasterlies should fill in for your journey to the Islands.

However, if your voyage plan includes sailing the South Pacific islands, Hawaii might not be the best place to start. Instead, the favored route to get into the South Pacific is following the coastline and making your first landfall in the Galapagos Islands.

It is also sometimes favorable to travel directly from California to the Marquesa Islands. The choice depends on the time of year and the sailing conditions of the season in question. Many cruisers choose to overwinter in Mexico, which allows time to explore along the way without rushing their Pacific circuit.

South Pacific Routes

Either way, the Marquesas Islands mark the entry point for most cruisers into French Polynesia. This route is commonly called the Milk Run because the sailing is tropical and downwind—and nothing could be easier.

Once inside the country, it is a few days’ sail to explore another island group. With the capital city Papeete, Tahiti is part of the Society Islands. Many cruisers also love exploring the more isolated Tuamotus with their low lying islands, coral atolls, and white sand beaches.

From Tahiti, boats can either continue westing towards New Zealand or Australia or return to home via Hawaii.

There are many other island nations to explore while sailing Pacific islands one after the other. Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands, and Vanuatu are cruiser favorites. After the long passage to the Marquesas, the week-long passage between countries will seem like nothing at all.

Eastbound Pacific Ocean Sailing

Sailing back to North America from the South Pacific isn’t as straightforward as you might think. Due to the prevailing winds, you cannot simply turn around. And sailing east across the Pacific is done far less often than sailing west is. Remember, most circumnavigators continue west from Australia into the Indian Ocean.

The solution is to complete a circuit sail across the Pacific Ocean. From those exotic islands south of the equator, the next stop will be somewhere due north of it in the North Pacific. The most common spot to regroup for the final leg home is Hawaii.

Northern Route

If you are already farther west or want to explore Fiji and Japan, you don’t have to go via Hawaii. Instead, you can take a high-latitude route across the North Pacific that will end in Alaska or the Pacific Northwest.

Hawaii to the West Coast

While that route might sound adventurous, you can generally make it with favorable winds. A layover in Hawaii might actually be more problematic.

You see, a course from the South Pacific to Hawaii will encounter northeast winds once north of the equator. Leaving Hawaii, you must plan the voyage to take into account the precise location of the North Pacific High. It’s the driving force that produces tradewinds in the area.

Cruising Across the Pacific – The Ultimate Nautical Adventure

Who doesn’t have fantasies of island hopping their way on a Pacific Ocean crossing? Sailing the South Pacific islands is the life-long dream of many sailors.

If you’re dreaming of planning passages to distant lands, pick up a copy of Jimmy Cornell’s World Voyage Planner. Inside, you’ll find tons of charts and explanations about voyaging from anywhere to anywhere.

Prices pulled from the Amazon Product Advertising API on:

Product prices and availability are accurate as of the date/time indicated and are subject to change. Any price and availability information displayed on [relevant Amazon Site(s), as applicable] at the time of purchase will apply to the purchase of this product.

Pacific Sailing Routes FAQs

How long does it take to sail across the Pacific?

The Pacific is the world’s largest ocean, so it should come as no surprise that crossing it is an enormous undertaking. As a result, most sailors choose to cross in hops, and the longest leg is from the Galapagos to the Marquesa Islands in French Polynesia. That leg takes between 17 and 25 days for most average cruising sailboats.

But of course, this leg is only about one-third of the way across the entire Pacific. From the Marquesas, most vessels continue westbound to Tahiti and then on to Fiji and New Zealand or Australia.

This entire trip usually takes around six months, accounting for stopovers and weather planning. Remember that boats usually try to avoid sailing during the South Pacific typhoon season, from November to May.

How safe is it to sail across the Pacific?

Safety is a relative term, so it’s impossible to say precisely how safe it is to sail across the Pacific. It’s like asking how safe is it to cross the street or drive on the interstate? It can be done safely if you are careful, of course, but there is always some amount of risk involved.

Dozens of cruising vessels make the passage from the west coast of the Americas to French Polynesia and beyond annually. You can mitigate many risk factors by planning the trip carefully, avoiding bad weather seasons, and keeping your boat in tip-top seaworthy condition.

The safety of a boat at sea always comes down to the seamanship of the skipper and crew. Good seamanship and sound decision-making makes for a safe voyage.